November 16, 2023

November 16, 2023

MDOT has fallen short of its own goals for safety in every year since 2012, and of full compliance with laws and policies that LMB advocated for, especially Complete Streets. Since 2009, more than 16% of deaths on Michigan roads have been people walking or biking. We need to hold MDOT accountable for safety, to push against its own inertia and make changes – radical changes if necessary – that move us toward zero deaths.

We know that MDOT can do more to protect the safety of low-impact travelers on foot or bike. We’ve got ideas and evidence. And to make sure these also get attention, we’d like your help.

Please take a few minutes to read our open letter to MDOT director Brad Wieferich, and if you agree, add your name by Nov. 30 (and ask your friends to do the same!) We’ll present the letter and signatures at the beginning of December.

– – –

November 2023

Director Wieferich,

At this time of year, we pause to remember loved ones who are no longer with us. For too many families in Michigan, this includes loved ones killed in a traffic crash. In every year since 2009, more than 16% of these deaths in Michigan have been people who were walking or biking.

A representative example: in East Lansing, a driver struck and killed a young man crossing Michigan Avenue (M-143) in the early morning hours of November 5, 2023. Sal Vackaro of Oxford survived the horrific shooting at his high school but lost his life on a Michigan road.

We appreciate MDOT’s commitment to safety and moving “Toward Zero Deaths.” However, we question whether MDOT has truly operationalized this goal and the significant changes in its engineering culture that will be needed to reach it. The status quo has failed. Traffic deaths have exceeded the goals set in Michigan’s Strategic Highway Safety Plans in every year since 2012:

Furthermore, MDOT’s compliance with state law intended to improve safety for people who walk and bike is lacking, as detailed below. We urgently request that MDOT take the following actions as an immediate demonstration of its commitment to safety for vulnerable road users:

- Implement the Shared Streets and Spaces program.

- Publicly release its five-year program for non-motorized infrastructure improvements.

- Update the MDOT Complete Streets policy to establish specific performance measures.

- Make Complete Streets the default on every MDOT freeway interchange and trunkline project.

- Provide a transparent process that incorporates public feedback for applying the Complete Streets policy.

- Offer a model Complete Streets policy.

- Support better data gathering for bike and pedestrian infrastructure.

- Establish safer lane width and curb radius standards on urban arterial roads.

- Account for the co-benefits of infrastructure projects that promote walking and biking.

A detailed rationale and background for each of these requests follows:

1. Implement the Shared Streets and Spaces program. As one of the primary advocates for the establishment of this program, LMB is available and eager to serve in an advisory role on its design and delivery. We ask MDOT to move urgently to implement it.

1. Implement the Shared Streets and Spaces program. As one of the primary advocates for the establishment of this program, LMB is available and eager to serve in an advisory role on its design and delivery. We ask MDOT to move urgently to implement it.

The FY2024 state budget signed by the governor on July 31 includes a $3.5 million line item in the transportation section for a Shared Streets and Spaces program, similar to the Massachusetts program, administered by MDOT to fund pedestrian and bicyclist safety improvements in Michigan communities. MDOT has not yet released a timeline for availability of this program.

2. Publicly release its five-year program for non-motorized infrastructure improvements. We ask MDOT to release the program it is required to prepare by state law and detail its planned investments in nonmotorized facilities.

MCL 247.660k(5) states that MDOT “shall prepare a 5-year program for the improvement of qualified nonmotorized facilities” to expend “at least 1% of the amount distributed… from the Michigan transportation fund” on an average annual basis.

The Five-Year Transportation Program (5YTP) does not currently include a breakout of nonmotorized facility expenditures. When LMB asked in a comment on the 5YTP, “Has MDOT met the 1% requirement as an average over the past 10 years? Is a full summary of these projects and their costs available?” we received a response that claimed without supporting detail that the “1% non-motorized requirement [is] an estimated $50 million or less, which MDOT has and will likely continue to exceed.” MDOT has not delivered the level of transparency and accountability that citizens expect for these funds.

3. Update the MDOT Complete Streets policy to establish specific performance measures, collect data on them on a regular timeline, and publish the data on a regular basis. MDOT is currently preparing to update its Complete Streets policy. We ask that any new policy include clear means to measure progress.

The current MDOT Complete Streets policy adopted in 2012 requires an annual progress report to the State Transportation Commission, but does not define performance measures, data collection responsibilities, or accountability mechanisms if these reports do not happen. These reports have not happened in recent years; none of the STC meeting agendas available on the STC website from 2019 through 2023 show a Complete Streets progress report.

The following steps for measurement have been identified by Smart Growth America:

- Establish specific performance measures across a range of categories, including implementation and equity

- Set a timeline for the recurring collection of performance measures

- Require performance measures to be publicly shared

- Assign responsibility for collecting and publicizing performance measures

Success for an updated Complete Streets policy will also require ongoing efforts to provide proper training and reinforcement of the policy with MDOT leadership and employees in Lansing as well as personnel at regional Transportation Service Centers (TSCs.) If no one is trained in or held accountable for the revised policy, then no one will care about following the revised policy.

4. Make Complete Streets the default on every MDOT freeway interchange and trunkline project.We ask MDOT to provide current best practice accommodations for pedestrians and bicyclists in every interchange and at every overpass or underpass as a default.

MDOT does not consistently take responsibility for implementing current best practices when upgrading their own facilities and addressing access and safety issues caused by their past investments.

MDOT's freeways bisect communities and create impenetrable barriers for nonmotorized users between key destinations, yet any efforts to bridge or go under freeways are seen as a nonmotorized investment to be paid for with nonmotorized-specific funds. Even in urbanized and suburban areas, communities need to lobby MDOT to get facilities incorporated, are expected to help pay for them (such as the non-motorized pathway at the I-96 / Grand River interchange in Brighton), and in many cases are required to maintain them. The freeways created the problem, and funds allocated towards freeways should be used to fix the problem.

MDOT trunklines can be almost as disruptive to community cohesion as a freeway, yet safe pedestrian and bicycle facilities take a back seat to motor vehicle travel, and the cost of any improvements come from TAP and local funds.

MDOT should instead employ the principles of Complete Streets, where accommodation is the default and a strong case must be made to not include accommodation, with the decision documented and signed off by an accountable senior administrator. MDOT should further take the principles of an ADA Transition plan: proactively look at where historical infrastructure investments prohibit or inhibit travel and create an action plan to fix those areas.

5. Provide a transparent process that incorporates public feedback for applying the Complete Streets policy, especially to measures that may increase safety for motorists at the expense of safety for bicyclists, like J-turns and rumble strips. We ask that MDOT engage with regional advisory groups such as the Traffic Safety Network groups or with the PBSAT to establish a process for applying its Complete Streets policy to projects such as these.

5. Provide a transparent process that incorporates public feedback for applying the Complete Streets policy, especially to measures that may increase safety for motorists at the expense of safety for bicyclists, like J-turns and rumble strips. We ask that MDOT engage with regional advisory groups such as the Traffic Safety Network groups or with the PBSAT to establish a process for applying its Complete Streets policy to projects such as these.

In several locations around Michigan, MDOT has chosen to install J-turn (or Restricted Crossing U-Turn) intersections where low-traffic rural roads intersect with high-traffic roads such as US-23, M-99 or US-131. These intersection designs can increase safety for drivers. However, by neglecting to offer accommodation for bicyclists or pedestrians at these intersections, MDOT has increased risk for vulnerable road users by forcing them to travel along the shoulders of the high-traffic roads, and disregarded the specific guidance in NCHRP Research Report 948. LMB engaged with the State Transportation Commission regarding these in early 2023, after several had already been constructed. More were added in the summer of 2023, including one only a quarter mile from Park Elementary School at Moorepark Road and US-131, between Kalamazoo and Three Rivers. MDOT’s current Complete Streets policy is not being applied to the planning and design of these intersections in any visible manner.

Similarly, while MDOT claims 3,175 miles of paved shoulders as a key part of its non-motorized transportation efforts, it has also installed rumble strips in the middle of many of these shoulders, rather than along the white line, significantly reducing the usable width of the shoulder for bicyclists. Entering a rumble strip at high speeds (such as on a downhill) merely warns drivers but presents a crash risk for bicyclists.

6. Offer a model Complete Streets policy, as required by state law. We ask MDOT to develop and make available a model policy demonstrating best practices for use by municipalities and counties.

MCL 247.660p(2) states that “the state transportation commission shall… develop a model complete streets policy or policies to be made available for use by municipalities and counties.”

No model policy is currently provided by MDOT or the State Transportation Commission. Perhaps as a result, few Michigan communities have kept pace with the best in the nation. No Michigan communities were recognized in Smart Growth America’s most recent “Best Complete Streets Policies” lists in 2023, 2018, 2017, or 2016. A high-quality model policy, such as one based on Tucson’s award-winning policy, would encourage Michigan communities to raise their standards and pursue best practices.

7. Support better data gathering on bike and pedestrian infrastructure. We urge MDOT to support efforts to create an asset management council with responsibility for multimodal facilities.

7. Support better data gathering on bike and pedestrian infrastructure. We urge MDOT to support efforts to create an asset management council with responsibility for multimodal facilities.

The MM2045 long-range transportation plan, approved in Nov. 2021, includes the following in its active transportation section: “Currently, with more than 600 road agencies and thousands of townships and parks departments all involved in building out the [active transportation] network, having these various entities track and report their inventory has not been possible. Therefore, there is not a means to estimate the inventory that exists for these facilities by type, as a policy does not exist requiring asset management and inventory of multimodal facilities at statewide, regional, or local levels.” Two years later, this is still true.

The Transportation Asset Management Council is a successful model for inventory and asset management of Michigan’s roads. Legislative action in 2024 could create a new asset management council with multimodal jurisdiction.

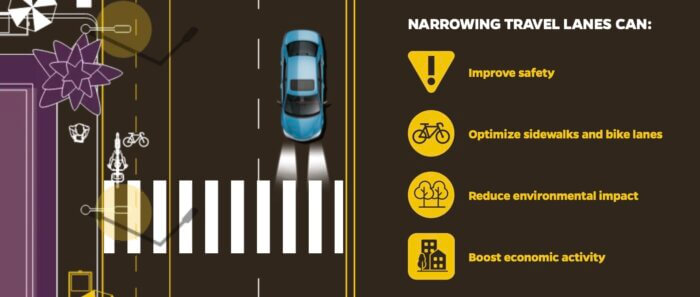

8. Establish safer lane width and curb radius standards on urban arterial roads. We ask MDOT to target urban high-risk areas for vulnerable road users, as identified in the Western Michigan University study, for immediate lane narrowing interventions.

A recent study released by Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, “Narrow Lanes Save Lives”, found that in cities “roads with 10–12-foot lanes at 30-35 mph speed limits have a significantly higher number of crashes compared to those with 9-foot lanes. Narrowing lane widths at these speeds provides city leaders with an opportunity to improve safety for all roadway users.”

MDOT controls many major urban arterial roads. Setting a default of 9 or 10-foot lanes rather than 11 or 12-foot lanes on these roads, beginning immediately, would save lives at relatively low cost.

9. Account for the co-benefits of infrastructure projects that promote walking and biking. We ask that MDOT move to estimate co-benefits in its transportation planning to better account for the full benefit of policies and investments that support walking and biking.

In the Fifth National Climate Assessment, Chapter 13.3, Sustainable Transportation, finds: “A carbon-free, sustainable, and resilient transportation system would have societal benefits beyond reduced climate change impacts, potentially leading to improvements in air quality, physical fitness, incidence of cardiovascular and respiratory disease, mental health, crash rates, noise pollution, social equity, ecosystems, biodiversity conservation, energy independence, and the economy. When these co-benefits are considered, the benefits of GHG mitigation actions in the transportation sector far outweigh the costs. ... Integrating co-benefits into transportation policies and planning at multiple scales (e.g., neighborhood, urban, national) can create additional appeal for reducing transportation-sector GHG emissions for both decision-makers and the public.”

The NCA offers the Integrated Transport and Health Impact Model (ITHIM) and Health Economic Assessment Tool (HEAT) as two means of measuring the economic value of these co-benefits.

– – –

We recognize that MDOT is a large and complex organization, and that major decisions and policy changes require time. These actions are discrete, manageable, and timely steps that can be advanced immediately to protect the lives of Michigan citizens, especially people who bike, walk and roll.

Categorised in: Uncategorized